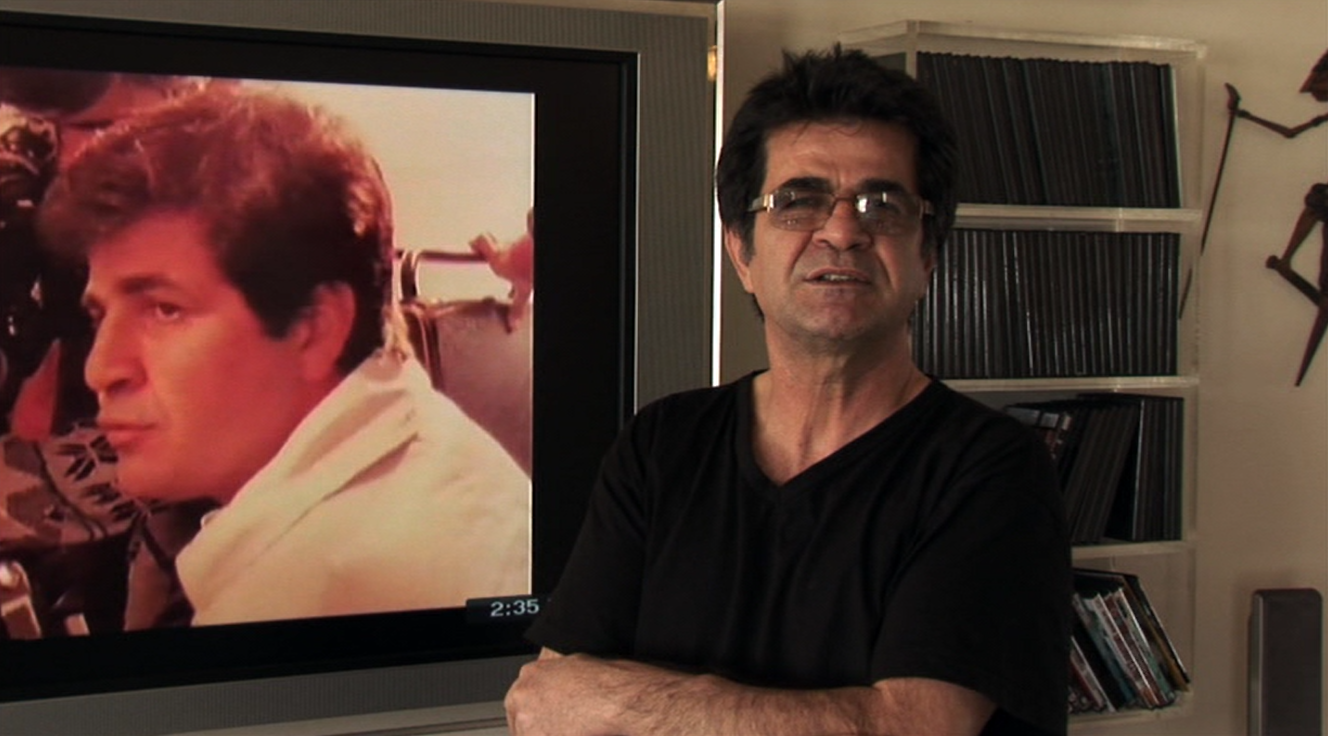

Cobb (1994, Ron Shelton)

Uncertain whether it aspires to be a farce or a tragedy, Cobb matches the hubris of its titular slugger and stretches for the pair, paradoxically emerging as callous and sentimental, despite attempts to impart emotional complexity. While the truth of its tabloid source material is eternally debatable, Ron Shelton’s admiration for the outfielder is not, making each uncomfortable shift in tone an unspoken justification for the violent mood swings of an amoral athlete. By laughing off aberrant behavior as eccentricity, Shelton buys into the cult of personality, mirroring a reluctance to rebuke celebrity malfeasance that has contaminated popular culture.

Unfurling in a newsreel-style montage, the film commences at the height of turn-of-the-century nostalgia, focusing on journalist Al Stump (Robert Wuhl) and his clique of outspoken beat reporters. Tucked away in a dimly-lit Angeleno dive, the roundtable debates sports’ superlatives, shouting out favorites like floor brokers at the New York Stock Exchange. Despite his soft-spoken demeanor, Stump is the most career-driven of the rowdy bunch, gladly leaving his post at the bar to accept an open-ended invitation from aging hardball icon, Tyrus Cobb (Tommy Lee Jones).

Inadvertently assuming the role of transcriber, Stump acts as middleman for Cobb’s blend of revisionist history, relinquishing his authorial voice at the cock of the power-hitter’s Luger pistol. The hyperbole of the fallen star’s tall tales are matched in absurdity by Shelton’s permissiveness, presenting Tommy Lee Jones with carte blanche to chew scenery, dulling each act of wild-eyed brutality by conveying an air of slapstick irrelevance.

A snowbound, whiskey-soaked drag race to Reno embodies this triviality at its apex, cartoonishly painting Cobb as spirited reveler and Stump as his gobsmacked enabler. Wuhl’s gesture-heavy acting does little to temper Jones’ excess, welcoming every maniacal bender and bout of violence with a reciprocal schmaltziness. Sadly, his intermittent narration, which could have benefitted from some mannered oration, is as stilted as his acting is melodramatic.

The tone is as manic as the lead performances, intentionally wavering between madcap and maudlin to the point of utter incoherence. Efforts to wrangle with the polar opposites of a complicated man, particularly the gulf between his talent and depravity, are abandoned for a gratuitous subplot that further uncovers the film’s decadence, recklessly veering from meet cute to sadistic sexual violation within minutes.

If Shelton had allowed the rape scene to have a ripple effect on the rest of the narrative, it would have been less jarring and incongruous, but left as a vignette in a film chock-full of them, it loses all resonance to a concluding revelation that pardons a long-suffering “hero.” Overwhelmed by this disingenuity, Shelton’s attempts at witty discourse and photographic majesty are rendered moot, stranding a handsomely-mounted character study somewhere between compelling and catastrophic.

Cobb (Warner Bros. Pictures, 1994)

Directed by Ron Shelton

Written by Al Stump (biography) and Ron Shelton (screenplay)

Photographed by Russell Boyd